What is Expressive Aphasia?

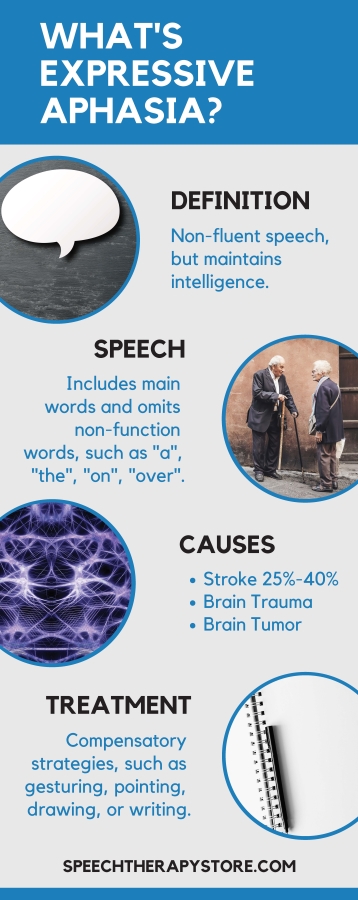

Expressive aphasia, also known as Broca’s aphasia or non-fluent aphasia, is a type of aphasia. Individuals with expressive aphasia have a loss of speaking fluently or writing fluently.

Speech can appear very effortful. Finding the right words or producing the right sounds is often difficult. Although they struggle to speak fluently their comprehension can be mostly retained with some difficulties understanding complex grammar.

A person with Broca’s aphasia may understand speech quite well. Especially when the grammar structure is simpler. For example, the sentence “Max bought Jane a candle.” may be easy to understand while the sentence, “The candle was given to Jane by Max.” may impact the comprehension of who gave the candle to whom due to the more complex grammar.

People with expressive aphasia often produce limited short utterances with less than four words. However, in very severe cases the person might only speak in one-word sentences.

Speech often includes main content words and deletes words with grammatical importance but little actual meaning, such as articles (the, a), prepositions (on, under), or pronouns (he, she). The individuals’ message may be clear but their sentence will not be grammatically correct.

For example, the doctor asked the patient, “Could you tell me what you have been doing at the hospital?” Patient, “Yes, sure. Me go, er, uh, P.T. (physical therapy) none o’cot, speech…two…times…read…r…ripe…rike…uh…write…practice…get…ting better.”

Please talk to your expressive aphasia patients. Imagine understanding everything, following all commands extensively, & not being able to communicate. Don’t just stand around in silence. #JustNeuroThings

— Nurse Mikay, BSN, RN, SCRN (@NurseStarling) January 3, 2018

History

Paul Broca, a French neurologist scientist, first identified expressive aphasia in 1861. When he began examining the brains of deceased individuals with speech and language disorders, which resulted from brain injuries.

Broca discovered that language was located in the ventroposterior portion of the frontal lobe, now known as Broca’s area.

He first discovered this in 1861 when he heard of a patient by the name of Louis Victor Leborgne who had a rapid loss of speech and paralysis but still had the ability to comprehend. The patient became nicknamed “tan” because that was the only word he could say clearly. Once the patient passed away Broca performed an autopsy. As Broca had predicted the patient had a lesion in the frontal lobe on the left cerebral hemisphere. Broca then went on for the next two years to autopsy 12 other patients to support his findings.

One important difference Broca made was that expressive aphasia is not due to the mouth’s loss of the motor ability to produce words, but rather the brain’s loss of the ability to produce language.

Around the same time as Broca’s discovers a German neurologist by the name of Carl Wernicke. Wernicke was also studying the brains of patients with aphasia post-mortem. Carl Wernicke discovered the region known as Wernicke’s area. Both Broca and Wernicke came to discover that brain functions are localized to specific areas of the brain. However, it was Wernicke who realized that there was a difference between aphasia patients with those who couldn’t produce language, expressive aphasia, and those who couldn’t comprehend language, receptive aphasia. Receptive aphasia, also known as Wernicke’s aphasia, is characterized as impairments in language comprehension and has damage to the more posterior region of the left temporal lobe.

Causes

- Stroke or brain injury: The number one cause of aphasia is a stroke or a brain injury. According to the National Aphasia Association, about 25% to 40% of stroke patients will experience some form of aphasia.

- Brain infection

- Brain tumor

- Dementia

- Alzheimer’s disease

About 180,000 Americans acquire aphasia each year. Aphasia affects about two million Americans making it more common than cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or Parkinson’s Disease. Despite these facts, most people have never heard of aphasia before.

Expressive aphasia is most commonly caused by a stroke in the Broca’s area or the area surrounding Broca’s area. However, some stroke patients experiencing expressive aphasia have had strokes in other areas of the brain.

Patients with acute brain lesions experience classic symptoms of expressive aphasia. The patients with more widespread lesions and a variety of symptoms are more likely to be classified as global aphasia.

In some cases, aphasia is due to epilepsy or other neurological disorders.

Different Types of Aphasia

- Expressive Aphasia or Broca’s Aphasia (non-fluent): Patients with expressive aphasia know what they want to say. However, they struggle to form complete sentences with appropriate grammar. They often delete words with little to no meaning, such as pronouns (he, she), articles (a, the), or prepositions (on, over).

- Example speech: For example, a patient with expressive aphasia might say, “Truck…hit…boom!” Although this is not a complete sentence you can get the main idea of what this patient is trying to say.

- Comprehension: In addition, a person with expressive aphasia can, for the most part, comprehend language. They do struggle to comprehend complex grammar. For example, if you said, “That man took the candy from the children.” A patient with expressive aphasia might be confused who took the candy from whom. Written language is impacted the same way that spoken language is impacted.

Here is a short video of a young woman who experienced a stroke at the age of 18 and is now experiencing expressive aphasia. Want to see how much progress she has made since this video? Be sure to watch the second video in this post under the heading prognosis to see how far she has come after 9 years post stroke.

- Receptive Aphasia or Wernicke’s (fluent): A patient with receptive aphasia can hear words or read print. But they may not understand what is being said or what they are reading. They will often take language literally. A person with receptive aphasia may say words that don’t make sense.

- Speech sample: For example, for the word napkin, they might say, “milgbe”. They are able to string words together and produce long sentences. However, they are often meaningless words that don’t make any sense making their speech not understandable. They often produce nonsense or irrelevant words.

- Anomic Aphasia: A person with anomic aphasia struggles with word-finding. This will affect both speaking and writing. The inability to find words is called anomia. Anomic aphasia is a milder form of aphasia where the individual has fluent speech but experiences word retrieval failures. They will often leave out major nouns and verbs in a sentence.

- Speech Sample: For example, instead of saying, “I will watch Matlock in the living room sitting in my favorite chair,” the patient might say, “I will watch in the in my.”A patient with anomic aphasia can understand written and spoken language very well.

- Global Aphasia: Global aphasia is the most severe form of all the aphasia types. It is when the stroke affects a large section of the front and back areas of the left hemisphere. It is most commonly seen right after someone experiences a stroke. A patient with global aphasia will experience difficulty with speaking and comprehending language. This means the person is also unable to read or write. Difficulties include only speaking a few words at a time, only understanding some words, difficulty understanding or forming words and sentences. A person with global aphasia often struggles to communicate effectively.

- Primary Progressive Aphasia: A patient with primary progressive aphasia is experiencing a rare disorder in which the patient will slowly lose their ability to read, write, speak, or comprehend language. A patient who has aphasia due to a stroke may improve with therapy, however, there is no treatment to reverse primary progressive aphasia. A person with primary progressive aphasia can use other ways to communicate other than speech, such as using gestures. Many patients benefit from a combination of speech therapy and medications.

Manual Language and Aphasia

A patient with aphasia who is deaf and using a manual language, such as American Sign Language (ASL) will have interruptions to their signing abilities. For example, in spoken language, a patient with aphasia might say, “nagkin” instead of “napkin” while in ASL the error might be observed in movement, hand position, or morphology.

Diagnosis

- A physician: A diagnosis of expressive aphasia is often first acknowledged from a physician who is treating a patient for damage to the brain, a stroke, or tumor. A Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) scan can help discover the presence of lesions on the brain. The physician will complete some simple assessments to get a basic understanding of the patient’s ability to produce and comprehend language. A physician will then refer the patient to a speech-language pathologist who will complete a full comprehensive battery of tests.

- Western Aphasia Battery: One commonly used test to diagnose a patient with aphasia is the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), which looks at auditory comprehension, naming, spontaneous speech, and repetition.

- Locate lesions: To locate the lesion to identify the specific type of aphasia and assess the patient’s current language abilities a commonly used test is the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE).

- Predict outcomes: In order to predict a patient’s potential outcomes, the Porch Index of Communication Ability (PICA) can be used.

- Identify target skills: The following tests Assessment for Living with Aphasia (ALA) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) can help a speech therapist identify target skills to work on with the patient.

- Informal testing: Other than just formal testing it is important to include informal testing and information gathering. For example, interviewing the family and patient about previous occupations, hobbies, interests, likes, and dislikes can help the therapist learn about the patient and what to focus on during recovery. Completing observations can help the speech therapist know where to start therapy. In addition, the patient’s physicians, medical records, and nursing staff can also provide helpful information to help guide recovery therapy.

- Deaf and use manual sign language: When it comes to diagnosing patients, who are deaf and use manual sign language, such as American Sign Language (ASL) diagnosis is made based on information gathered from family and friends about the patients signing abilities pre- and post- damage to the brain.

Treatment

There isn’t one size fits all treatment when it comes to treating expressive aphasia. Instead, treatment plans will be individualized based on the assessment findings, the age of the patient, the cause of the brain injury, and the position and size of the brain lesion. For example, a patient with expressive aphasia due to a brain tumor may need surgery and then post-surgery their aphasia may improve. In those patients who experience expressive aphasia due to a stroke, will most likely go through a period after the stroke of spontaneous speech and language recovery.

Therapy will consist of sessions with a speech-language pathologist to focus on increasing the patient’s ability to speak and communicate. In order to compensate for language, the patient will also be taught compensatory strategies, such as gesturing, drawing, speak slowly, using phrases and words that are easier to pronounce. Communication treatment is individualized on the patient’s priorities and focuses on increasing everyday communication with the patient’s family and caregivers.

A patient with expressive aphasia may also find it helpful to carry a card with them that lets them explain to strangers that they have aphasia and what that means.

- Melodic Intonation Therapy: Melodic intonation therapy (MIT) began when patients with expressive aphasia could sometimes sing words or phrases that they normally couldn’t speak. It is thought that since our singing abilities are stored in the right hemisphere of the brain and this area normally remains intact for patients who experience a stroke that MIT therapy can help the patients with word retrieval and expressive language.

- Who benefits: MIT therapy is used with patients with chronic non-fluent expressive aphasia.

- Purpose: The purpose of MIT is to use the right hemisphere to compensate for the loss of language in the left hemisphere. It has been shown that patients with a unilateral, left hemisphere stroke, non-fluent chronic expressive aphasia, and who are motivated are good candidates to use MIT to increase their intelligible speech output.

- Therapy: It is recommended that therapy is five days a week for about 1.5 hours a day. Therapy begins with simple or short phrases which are broken down into high and low pitch syllables. As therapy increases the patient will move to longer phrases using a natural melodic speech with continuous voicing. In addition, a patient may be encouraged to tap the syllables with their left hand to help with the rhythmic speech.

- Constraint-Induced Therapy Constraint-induced aphasia therapy (CIAT) is based on constraint-induced movement therapy that was first developed by Dr. Edward Taub at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Dr. Edward Taub discovered the idea of “learned nonuse”. For example, learned nonuse is when a patient with a physical impairment compensates for the lost function of one limb by using other means such as an unaffected limb. In constraint-induced movement therapy, the patients’ unaffected limb is constrained with a glove or sling forcing the patient to use their affected limb. There are three main principals of constraint-induced movement therapy to counteract learned nonuse of the affected limb.

- The three principals: Constraint – to avoid compensation by tying back the good limb. Forced use – require the use of the affected limb by placing the patient in forced situations where they need the affected limb in order to be successful in order to achieve a meaningful goal, such as acquiring food. Massed practice – force use every day and all day long.

- Principals Explained: When the principals are applied for speech therapy of a patient with aphasia the constraint is avoiding compensatory strategies, such as gesturing, drawing, or writing. The forced us is to only communicate through speaking and the massed practice is to have therapy for 2 to 4 hours per day.

- Therapy: Therapy often includes a language game using picture cards and encouraging only verbal skills in order to play the game and to refrain from using compensatory strategies.

- How CIAT differs from traditional therapy: CIAT differs from traditional therapy in that compensatory strategies, such as gesturing, drawing or writing should be avoided unless absolutely necessary. Best results have been seen in patients with chronic aphasia that has lasted over 6 months. It has been noted that improvements have continued even after a patient has reached a plateau and that the benefits of CIAT are retained long term. Most improvements are seen in those patients who undergo intense CIAT.

How A Person with Aphasia Can Help Facilitate Communication

- Inform conversational partners: A person with aphasia should plan on telling their communication partner that they have aphasia if they plan on having an in-depth conversation with that person. It should be a script that the patient has rehearsed and includes simple words and phrases.

- Provide feedback: The patient with aphasia should give their communication partners feedback in order to make their conversation more successful. For example, if the speaker is speaking too quickly or if the speaker is using too many complex sentences.

- Use visuals: Bring your empty item to the grocery store or bring the product label to show the store employee. When ordering at a restaurant point to the item on the menu.

- Use communication aids: For example, carry a piece of paper with the alphabet on it, carry pictures of common activities you do, such as ordering a cup of coffee. Another helpful communication aide was developed by Dr. Wilson Talley which is a business card that a patient with aphasia can handout to people to help them communicate. It communicates their name, emergency contacts, physician’s name, telephone number along with the following message:

“Aphasia is an impairment of the ability to sometimes use or comprehend words, usually acquired as a result of a stroke. Depending on where and to what extent the brain is injured, each person with aphasia has a unique set of language disabilities. I am not drunk or mentally unstable! It is NOT a loss of intelligence!”

This card can come in very handy if you get pulled over while driving.

![]()

Things to Keep in Mind

- The power of socializing: Research has shown that one of the best ways to recover from a stroke is to socialize. Socializing should begin right away on the road to recovery.

- Language versus intelligence: A distinction between the patient’s language and intelligence should be made.

- Can still think: A patient with aphasia can still think they just can’t say what they think.

- Still intelligent: People mistakenly think that the patient is no longer as intelligent as they once were.

- Struggles with language: A person with aphasia struggles to use language to communicate what it is they know.

Perpetually “mama bear protective” over the way people speak to my expressive aphasia patients. She’s got an issue speaking not understanding. For the love of god please drop the baby voice.

— Nurse Mikay, BSN, RN, SCRN (@NurseStarling) February 15, 2018

Prognosis

The majority of patients with expressive aphasia will experience the majority of their recovery within the first year following a stroke, brain trauma, or brain tumor. It also depends on the type of stroke. A patient with an ischemic stroke may experience recovery in the first few days and weeks. Then they may hit a plateau with a gradual slowing of their recovery from there. While a patient with a hemorrhagic stroke may experience a slow recovery in the first few weeks and then experience a quicker recovery which then stabilizes.

Other factors include the site and the size of the lesion. All of which will impact a patient’s recovery. In addition, one’s age, education, emotional state, personality, and motivation can all determine a patient’s prognosis of recovery.

Here is a short video of the same young lady in the previous video above. This video is taken nine years after her stroke at the age of 18 years old. You can see the amazing growth she has made over the years.

Conclusion

A person with expressive aphasia struggles to produce grammatically correct sentences. However, they still have the ability to comprehend most language.

Every year there are about 795,000 strokes and about 25% of those strokes are recurrent strokes. Learn Simple Ways to Avoid Another Stroke from happening.

Got questions? Leave a comment. Let’s chat!

References

ASHA Practice Portal. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved August 7,2017. Wilson Sarah J (2006). “A Case Study of the Efficacy of Melodic Intonation Therapy”. Music Perception. 24 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1525/mp.2006.24.1.23. ISSN 0730-7829.

Bakheit, AMO; Shaw, S; Carrington, S; Griffiths, S (2007). “The rate and extent of improvement with therapy from the different types of aphasia in the first year of stroke”.

Broca, Paul. “Remarks on the Seat of the Faculty of Articulated Language, Following an Observation of Aphemia (Loss of Speech)” Archived 17 January 2001 at the Wayback Machine.. Bulletin de la Société Anatomique, Vol. 6, (1861), 330–357.

“Broca’s Aphasia – National Aphasia Association”. National Aphasia Association.

Brookshire, Robert (2007). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. ISBN 978-0323045315.

Common Classifications of Aphasia. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Aphasia/Common-Classifications-of-Aphasia/

Fancher, Raymond E. Pioneers of Psychology, 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990 (1979), pp. 72–93.

Fromkin, Victoria; Rodman, Robert; Hyams, Nina (2014). An Introduction to Language. Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. pp. 464–465. ISBN 1133310680.

Hicoka, Gregory (1 April 1998). “The neural organization of language: evidence from sign language aphasia”. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2 (4): 129–136. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01154-1.

Manasco, M. Hunter (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Marshall, Jane (15 June 2004). “Aphasia in a user of British Sign Language: Dissociation between sign and gesture”. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 21 (5): 537–554. doi:10.1080/02643290342000249.

Jump up toCommon Classifications of Aphasia. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Aphasia/Common-Classifications-of-Aphasia/

Meinzer, Marcus; Thomas Elbert; Daniela Djundja; Edward Taub (2007). “Extending the Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) approach to cognitive functions: Constraint-Induced Aphasia Therapy (CIAT) of chronic aphasia”. NeuroRehabilitation. 22 (4): 311–318.

Pulvermuller, Friedemann; et al. (2001). “Constraint-Induced Therapy of Chronic Aphasia following Stroke”. Stroke. 32 (7): 1621–1626. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.492.3416. doi:10.1161/01.STR.32.7.1621. PMID 11441210.

Purves, D. (2008). Neuroscience (fourth ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 0-87893-742-0.

Raymer, Anastasia (February 2008). “Translational Research in Aphasia: from Neuroscience to Neurorehabilitation”. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 51: 259–275.

Schlaug, Gottfried; Sarah Marchina; Andrea Norton (2008). “From Singing to Speaking: Why singing may lead to recovery of expressive language function in patients with Broca’s Aphasia”. Music Perception. 25 (4): 315–319. doi:10.1525/mp.2008.25.4.315. PMC 3010734. PMID 21197418.

Thompson, Cynthia K. (2000). “Neuroplasticity: Evidence from Aphasia”. Journal of Communication Disorders: 33 (4): 357–366.

Blair

Friday 12th of April 2019

It works very well for me

Luciana

Friday 5th of April 2019

I spent a lot of time to locate something similar to this